Our Moment in History

Our moment in history has been called the time of the “Great Bonfire“. You can picture 20% of the world’s population sitting around this fire piling on 1million tons of fossil fuels every hour. Burning an olympic size swimming pool of crude oil every 15 seconds. The remaining 80% watch from a far distance whilst the fuel gauge heads towards zero.

When historians look back at our time it will be defined as a brief moment of 2-3 generations that lived during the fossil fuel age. Our cornucopian belief that we will always come up with a solution and that there are no limits has blinded us from the truth that we are squandering the Earth’s resources and leaving little for future generations. Just think – half of all the CO2 that humanity has put into the atmosphere has occurred since 1980.

Energy is Everything

Energy is everything. No energy = No work. We know this when we are sick in bed or when the electricity goes out. Before the era of fossil fuels humanity was constrained by the limited amounts of energy that could be harvested from nature. The energy available to is was our own muscle power, wood, oxen, small wind and hydro and even human slavery.

This constraint acted like a governor on how productive we could be – in terms of how much food we could produce, how much housing we could build and how much infrastructure we could put in place. The discovery of fossil fuels at the beginning of the industrial revolution lifted that constraint and fuelled the growth of everything we see today.

The more energy we had the more productive we could be, and, the more productive we could be, the faster our economies could grow. Transport, trade, agriculture, population and even our financial institutions developed on the back of an ever increasing supply of fossil fuel energy.

The industrial revolution was really an energy revolution that enabled us to break free from the limits of nature. The civilisation we see today is as much a result of energy availability as a result of human ingenuity.

Anatomy of an Economy

A traditional economists view is that the inputs to an economy are capital and labour and that the outputs are saleable goods and services. Resources and energy are viewed as secondary inputs, are in abundance and any limitations will be overcome by science and innovation. Nobel prize winning economist, Robert Sollow, went so far as to say “the economy can in effect continue without the natural world”.

But of course the economy is a subset of the environment. All energy comes ultimately from the sun which we avail of through the exploitation of wood, wind, water etc and of course fossil fuels, which is ancient sunlight energy trapped over geological time in the form of oil, coal and gas.

Our economy is in essence a materials and energy processing system. The earth’s resources are transformed using high quality energy into goods and services and in the process waste is dispersed into the environment. The economy is therefore subject to the laws of nature and there are limits to how much energy and resources that the earth can supply and how much waste it can consume.

Exponential Growth

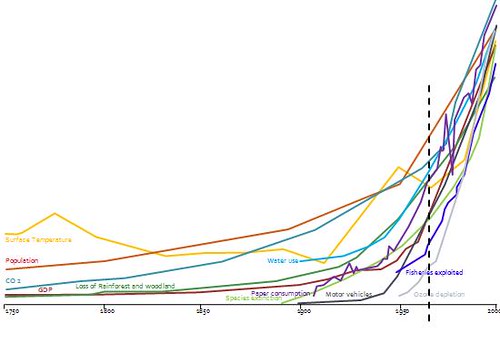

Our economies grow exponentially year on year. This means that each years growth is bigger than the previous years growth. Consequently each years demands upon energy, resources and the earth’s capacity to absorb waste also grow.

Consider that it has taken all of humanity for the industrial economy to reach its present size, yet at a 3% growth rate the global economy would double in just over two decades. Imagine twice the number of cars, televisions, houses, cities, motorways, airplanes and shipping. On a finite world its clearly not possible.

Yet, the background acceptance of ever continuing growth is never questioned. Investments in infrastructure, insurance, business expansion, savings and pensions assume that the future will always be bigger than the past.

Looking back over the last century it is not difficult to understand this assumption because it has been our lifetime experience. We have become so used to growth that we see the growth curve we are on as essentially flat and the way things should be. Contrast this to life before fossil fuels when growth was imperceptibly small with very little change from generation to generation.

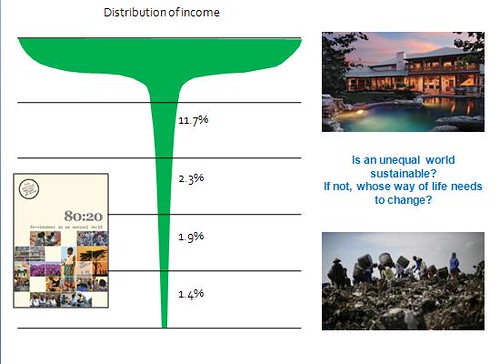

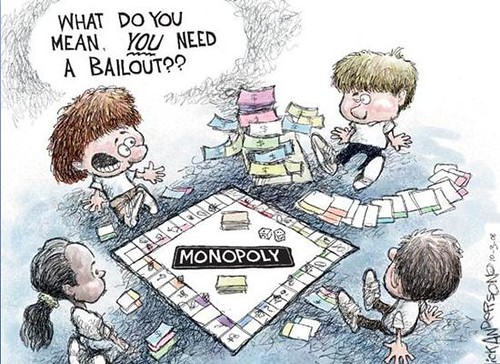

But inequality continues to grow

As humans we are predisposed to growth and the principle argument for growth is that the “trickle down” effect with “lift all boats” and that everyone will benefit. This has not happened. Wealth is being increasingly concentrated in the hands of the few both at home and abroad. In 1960 the income of the richest 20% was 70 times that of the poorest 20%. In 1990 the income of the richest 20% was 140 times that of the poorest 20%. In 1980 for every $100 added to the global economy $2.20 was added to those below the poverty line, by 1990 that figure had shrunk to 60cents.

David Korten, author of The Great Turning, in a recent article titled “After the Meltdown” posits that “Our economic and political system has produced a credit meltdown, a shrinking middle class, escalating food and energy prices, a dramatic decline in U.S. Manufacturing, billion dollar pay packages for hedge fund managers, sky-rocketing consumer debt, an unstable US dollar and the spreading collapse of the earth’s environmental system. By any measure, our economic system has failed”.

Constraints on Energy

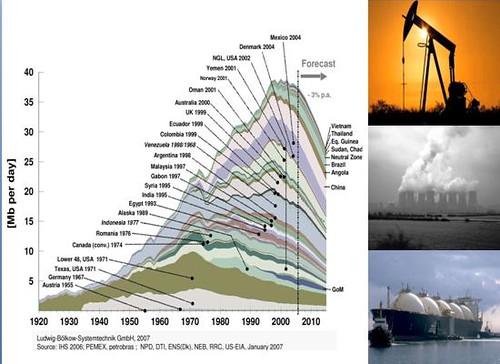

The world was endowed with approximately 2 Trillion barrels of conventional crude oil, and, over the last seventy years we have consumed about half. If we could continue at today’s rate we would consume the second half in only 33 years!

The problem, however, occurs around about now at the halfway point when production reaches a maximum and then goes into a steady decline. Given that many individual countries have already passed their peak of oil production it stands to reason that eventually the world will peak. Many independent geologists and oil industry experts forecast a peak and subsequent decline somewhere around 2012.

This will be followed by peak gas in 2025 and peak coal in 2030. This will have a dramatic effect on a global economy that is dependent on an increasing supply of cheap energy in order to grow.

Constraints on Resources

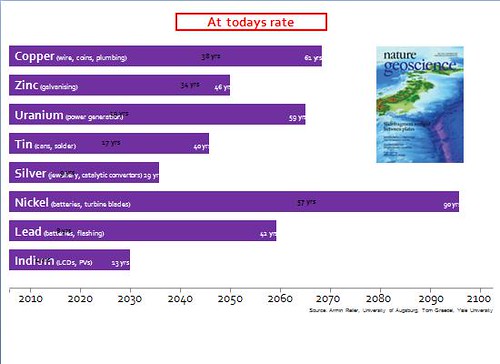

And its not just oil that we are running out of. Many key resources are in decline: biodiversity loss, top soil erosion, phosphate production, fresh water and aquifer depletion, world fish stocks and rain forests to name but a few.

Metals are almost as important to an industrial economy as oil as they are used to make machines and transport electricity. Many of the world’s metals are being consumed at voracious rates as countries such as China and India industrialise. According to a study in Nature GeoScience, at current rates, many key metals such as Tin, Zinc and Lead will be exhausted by mid-century. Indium, used in second generation Solar PVs will be exhausted in 13 years.

If the rest of the world consumed at even half the rate of the US many of these resources would be exhausted within the next two decades.

Constraints on Waste

There are many example of the earth’s waste sinks becoming overburdened but none is as serious as our pollution of the atmosphere with CO2, N2O and CH4 – the main greenhouse gases. By burning of fossil fuels, land use change and deforestation. CO2 concentration levels have risen by 35% since pre industrial times.

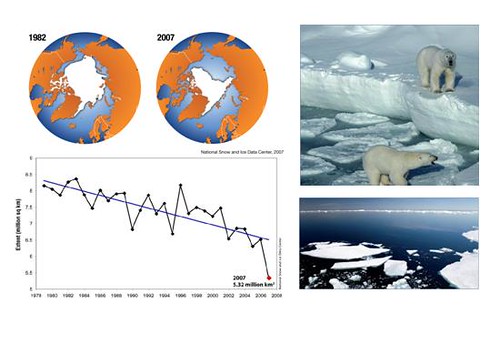

The Global Average temperature has increased by 0.8 °c but because CO2 is a long lived gas in the atmosphere (100years) and because of the enormous thermal inertia of the oceans we are committed to a further 0.8 °c temperature rise even if emissions are stopped today. Scientists fear going above 2°c because beyond this threshold positive feed-backs will occur which will cause further unstoppable warming.

The melting of the polar ice cap is a classic tipping point. Normally the ice reflects the incoming sunlight but as the ice melts dark seawater is exposed which absorbs more heat which melts more ice and so on. Recent scientific studies suggest that the polar ice cap may be ice free by 2012, much earlier than previously forecast.

Constraints on the Economy

Given the constraints of Energy, Resources and Waste it is hardly surprising that the global economy would sooner or later begin to falter. A declining energy and resource base equals a declining economy. Less in = Less out. Increased investments in managing waste (adapting to climate change) reduce output even further.

Furthermore, because our monetary system is debt based it has a particular vulnerability to economic decline and may in fact collapse. Apart from the 2-3% of actual notes and cash all money is created as interest bearing loans. If no new loans are taken out the money supply will shrink in a deflationary spiral as the old loans are paid off. To make things worse because all loans are interest bearing more money must be created year after year(through loans) in order to pay back the principals+interest and maintain the money supply. This means that the economy must grow from year to year. On a finite world this is not possible forever.

In all likelihood the current economic downturn will morph continually into the next. There may be a recovery from the current recession but this is unlikely to last long and will be nipped in the bud by declining energy supplies, rising costs and diminishing returns on investment. As economies cannot maintain growth claims on the future of economic growth in the form of debt, pension payments and investment returns will become unpayable. We need a new monetary system and a new steady state lean economy.

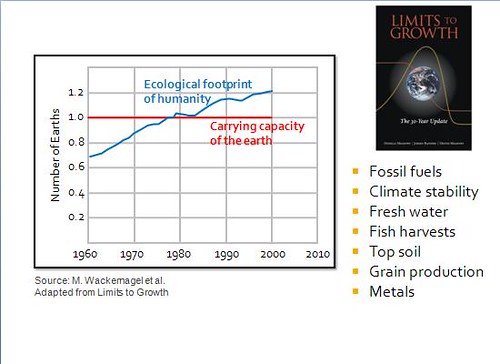

The Limits to Growth

Since the first oil shocks of the 70’s scientists and academics have been warning of the pressures that are being placed on the ecosystem and the finite nature of the earth’s resources. The Club of Rome’s 1973 Limits to Growth study showed how by the early part of this century the world would be facing serious limits to continued industrial growth and human expansion.

Peak oil is an example of a resource limit whilst Climate Change is an example of a pollution limit. Humanity has been overshooting the biosphere’s capacity to sustain our activities. The reason we have the illusion that everything is OK is because we’re using up what our children and grandchildren expect to inherit.

Today, it would take at least three Earths to sustain us if everyone had the lifestyle of people in the UK; five if we all lived like Americans. Even for the population of China to reach our patterns of consumption would require a second Earth. Given the limits to growth we need a fundamental rethink about how we live in the 21st century.

Where do we go from here?

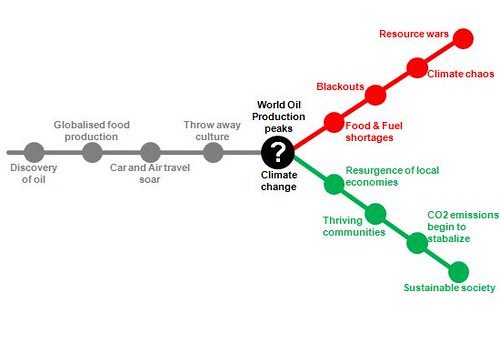

There are two pathways ahead. “Resource wars and Industrial Collapse” or “Controlled descent and thriving communities”. What Homer Dixon calls, “The Upside of Down”.

Sustainability in this context is not a lifestyle choice or a political standpoint but a sensible survival strategy for dealing with the converging challenges.

We cannot avoid a potentially very difficult long-term global economic and social transformation. It is a challenge that many other civilisations failed to meet as they ignored the warning signs of a contracting energy and resource base. The question is how to prepare communities for the change and how best to adapt to the transition resolutely, wisely and with foresight.